3 lessons from behavioural economics Bill Shorten's Labor Party forgot about

- Created: 2019-05-22T22:53:44+00:00

- Last Updated: 2019-05-22T22:55:08+00:00

"The Conversation is an on-line magazine where researchers can place summaries or engagement pieces about their particular areas of interest. I thought this recent article might be of interest given it's reference to thinking fast; thinking slow." - Brett Heyward

3 lessons from behavioural economics Bill Shorten's Labor Party forgot about

Three simple lessons from behavioural economics would have helped the Labor Party sell its economic credentials. www.shutterstock.com Tracey West, Griffith University

Three simple lessons from behavioural economics would have helped the Labor Party sell its economic credentials. www.shutterstock.com Tracey West, Griffith University

The Australian Labor Party’s 2019 election campaign showed a depth and breadth of economic policies rare for an opposition party to present. Its policy agenda was boldly extensive. But in developing these policies over the past five years, it seems Labor’s economic minds overlooked some fundamental principles of behavioural economics.

Had greater focus been put on these principles, it is possible Labor would have taken a different approach to selling its credentials, and succeeded in moving more voters its way.

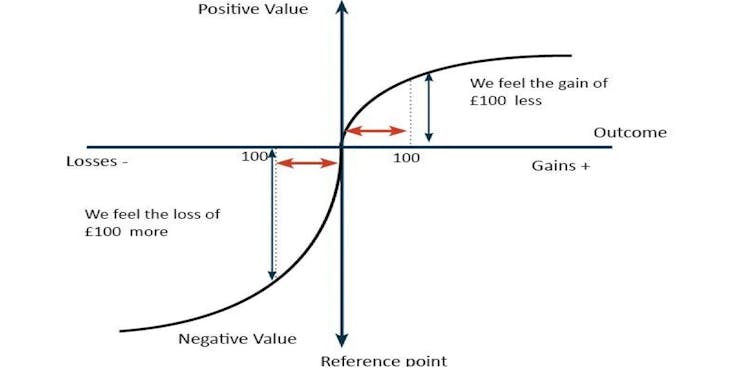

1. People are loss averse

Distinguished psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman demonstrated in the 1970s that losses have a profound psychological impact and people prefer to avoid them. In 1979 they published a paper proposing what they called “prospect theory” – that the pain a person feels from a monetary loss is greater than the pleasure felt from a monetary gain of the same value.

As Tversky and Daniel Kahneman put it succinctly: “Losses loom larger than gains.” This means, when faced with uncertain outcomes, most people prefer keeping the status quo to the risk of change.

Labor’s failure to persuade more voters they would gain more than they might lose under its reforms played to the Coalition’s advantage.

The government was able, for example, to make the most of Labor’s policy on negative gearing by playing on the chance all home values would fall, even though modelling suggested any fall would be minor.

Read more: Confirmation from NSW Treasury. Labor's negative gearing policy would barely move house prices

It did something similar with Labor’s franking credit, casting it as a “retiree tax”, and playing on fears that big promises to increase spending on welfare, health, education and wages might mean them losing money from other tax changes.

2. Limited decision-making

People’s decisions are limited by the amount of information they have – a concept known as bounded rationality – and giving them more information doesn’t necessarily help.

Our ability to pay attention to two or three things at the same time is much more limited than we think. We tend to be selectively inattentive, screening out information we perceive as unimportant, and preferencing information that confirms existing views.

Economists Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein argued in a 2002 article that bounded rationality demanded “libertarian paternalism” – limiting the choices offered to voters without eliminating freedom of choice.

Labor went another way – burying voters in an avalanche of policy prescriptions. Arguably it overestimated how much people would absorb, and diluted focus on a few key ideas.

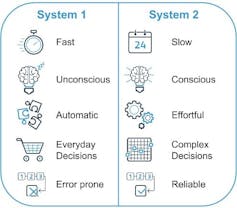

System 1 and 2 thinking. www.upfrontanalytics.com

System 1 and 2 thinking. www.upfrontanalytics.com

To understand and compare policy detail, according to economist and psychologist Daniel Kahneman, requires a deliberate and methodical approach – what he calls “System 2 thinking”.

But most media and social media deals in “System 1 thinking”, which responds instinctively to short slogans and repeated messaging.

What Labor failed to do was reconcile System 2 idealism with System 1 necessities.

3. Now is worth more than later

People place a higher value on the short-term over the long-term. From an evolutionary perspective, this bias has no doubt served us well, particularly in times past when the future was much more uncertain.

This disposition informs an important economic concept known as hyperbolic discounting – the tendency for people to increasingly choose a smaller reward sooner over a larger reward later.

Say, for example, you were offered a choice between taking $150 now or $160 in four weeks. Most people would take the $150.

But what if you were asked to choose between $150 in 48 weeks or $160 in 52 weeks? Research shows most people would then elect to wait the extra four weeks to receive the higher amount of money.

So Labor faced the problem of it promising to deliver benefits that might take decades to pan out, such as transitioning from fossil fuels to renewable energy, while the Coalition was offering immediate tax cuts and cheaper energy prices. Many Australians, we can imagine, preferred the more immediate benefits to the longer-term ones.

Whatever criticisms might be made about other aspects of the campaign, the Coalition’s messaging demonstrated an intuitive understanding of the behavioural biases of individuals.

From its strategy Labor could learn a lot.

Read more: Labor's election loss was not a surprise if you take historical trends into account ![]()

Tracey West, Lecturer in Behavioural Finance, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.